By Hunter Drohojowska-Philp

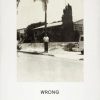

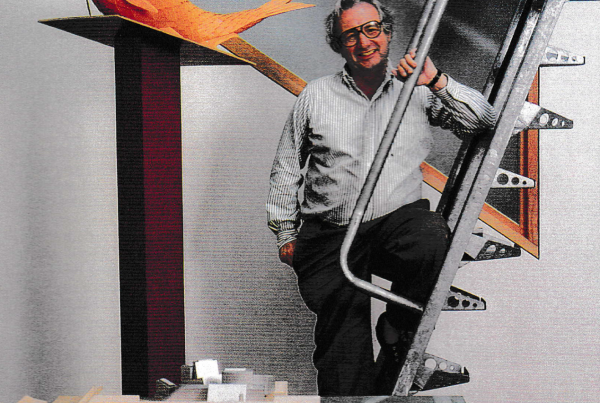

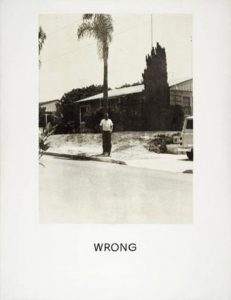

John Baldessari, “Wrong”, 1966-68

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

© 2009 John Baldessari

John Baldessari stayed present until the beginning of the new decade. He was 88 when he died at his Santa Monica home on January 2, 2020. 1/2/2020. He had to appreciate the clean symmetry of that date.

One of the slim advantages of writing about art is the opportunity to know, even befriend, great artists. Baldessari has been a big part of that for me since since the early 1980s, when I first wrote about him as a Conceptual artist.

He later told me that he hated being labeled a “Conceptual artist.” He added with gentlemanly concern that most artists feel like labels can’t capture the complexity or nuance or variety of their art. Conceptual art is particularly confining since it tends to bring to mind a dour collection of typed words and colorless photographs, a prioritization of thought over feeling or execution. Baldessari wound up making fun of the very discipline he helped create. Serious fun, as in his 1967 grainy photo emulsion print of a man standing in front of a palm tree and the word “Wrong.” At exactly that time, Baldessari began his long a career of doing the wrong thing, intentionally.

This strategy had evolved after Marcel Duchamp’s 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum, a show that had a profound effect on artists in Southern California but especially those, like Baldessari, with an inclination to philosophical speculation. After his first solo show at Molly Barnes Gallery, exactly the same month that Joseph Kosuth was showing across the street with Eugenia Butler, he found himself placed in that uncomfortable category of Conceptual artist, showing more in Europe and teaching, which wound up being a crucial aspect of his own practice. He told me he felt that when he was teaching, he was making art and when he was making art, he was teaching.

It was as a teacher in 1971 that he assigned students at Nova Scotia College of Art to repeatedly scrawl the punitive assignment in cursif, “I will not make boring art.”

I met Baldessari in the early 1980s in the way many of us did: through his students. He was a hugely important figure in the early years of Cal Arts, when artists as disparate as Lari Pittman, Mike Kelly and Christopher Williams attended. Even if he was not specifically their teacher, artists couldn’t help but absorb the notion of the “post-studio” curriculum he established.

My 2011 book Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s includes a chapter on Baldessari and others at the advent of Conceptual art on the West Coast because their first exhibitions were in L.A. in the late 1960s, just as the scene was changing. There is no doubt that Baldessari’s work was taking a position in opposition to the dominance of the Ferus gallery and artists who had gained attention for their Pop, assemblage or light and space orientations. Baldessari’s big canvases made without paint or brush, using photographs taken at random with texts executed by a sign painter was a way of taking a position on his future, not their past.

As Baldessari began showing regularly in Europe, not New York, he urged his students to pursue similar strategies to avoid seeking to fit into the competitive New York art scene, which historically had been oriented to painting.

Baldessari’s breakthrough solo show in L.A. was with Margo Leavin Gallery in 1984. The enlarged black and white cinematic photographs in shaped frames seemed a giant leap forward and Baldessari felt it. I wrote about him and that show for the L.A. Weekly

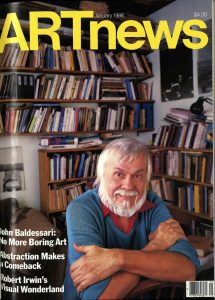

Two years later, I expanded it as a cover story for Artnews.

Around the same time, guest curator Wayne McCall organized a small show of that work for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and asked me for a small essay that I called Blasted Signifiers. The entire catalogue is about ten pages long. The work was baffling but not to important collectors and curators. It was the beginning of something big. I wrote about it for Harper’s Bazaar in 1990– Deconstructive Criticism.

Thereafter, I wrote about his work regularly including a story about the Ocean Park bungalow that he had renovated with gardens by Pamela Burton, furniture by Roy McMakin and an enormous bathtub to accommodate his six foot, seven inch torso. That custom-made bathtub was costly but he told me, “It’s expensive for a bathtub but not for a work of art, so I decided to think of it as art.” That is a rationalization I’ve used myself many times since.

Installation view of “Magritte and Contemporary Art The Treachery of Images”

Photo courtesy Museum Associates/LACMA

LACMA’s Stephanie Barron asked Baldessari to creatively install paintings by Rene Magritte with works of contemporary art influenced by him, especially the museum’s own 1929 painting The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe). What could be a better theme for him? In 2006, he designed a brilliant intervention by covering the gallery floors with custom made wall to wall carpet of pale blue with white clouds, literally reversing what is up and what is down.

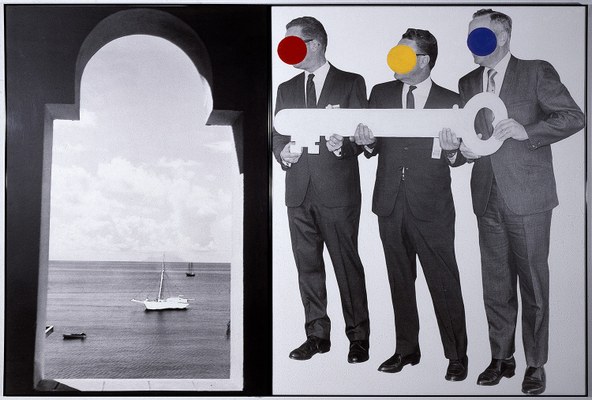

Collector Jordan Schnitzer, who has compiled definitive collections of prints by many great contemporary artists, published a catalogue with 140 prints by Baldessari in 2010. In my essay, I asked Baldessari about his decision to add large circle of color over the faces in his appropriated photographic works, directing the viewers attention towards marginal details. “In my work,” he said, “I found that I could be the master of my own universe and control what people see and pay attention to.”

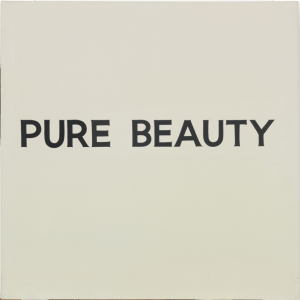

This was even more apparent when LACMA’s Leslie Jones and the Tate co-organized his retrospective Pure Beauty in 2016. He and his art were always evolving but always the same as he explored more deeply ideas that continued to fascinate.

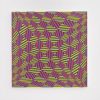

Pure Beauty 1966-1968, Acrylic on canvas © John Baldessari, Courtesy of Baldessari Studio and Glenstone

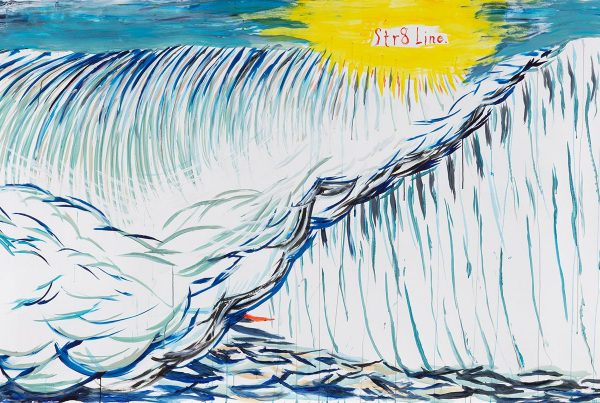

His last retrospective was a triumph and insightful: Learning to Read with John Baldessari at Jumex in Mexico City. The museum’s founder Eugenio Lopez Alonso credits Baldessari as a crucial influence in his interest in art and his collecting. English curator Kit Hammonds brought attention to Baldessari’s unwavering interest in the placement and meaning of language over 50 years. Around the same time, Baldessari showed his paintings, actual paintings, of emojis and texts at Spruth Magers.

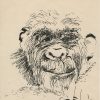

John Baldessari, “Key,” 1987

Two black & white photographs with vinyl paint; 152 x 213 cm

Courtesy the artist / Photo by Abigail Enzaldo

It’s strange how only specific quotes linger in the memory. At an opening at LACMA, almost everyone had left apart from Mike Kelley and Baldessari. I was talking with them and asked them something about the number of young artists making work that was so clearly under their influence. Baldessari simply shrugged and said, “Art comes from art.”