Raymond Pettibon’s Pacific Ocean Pop

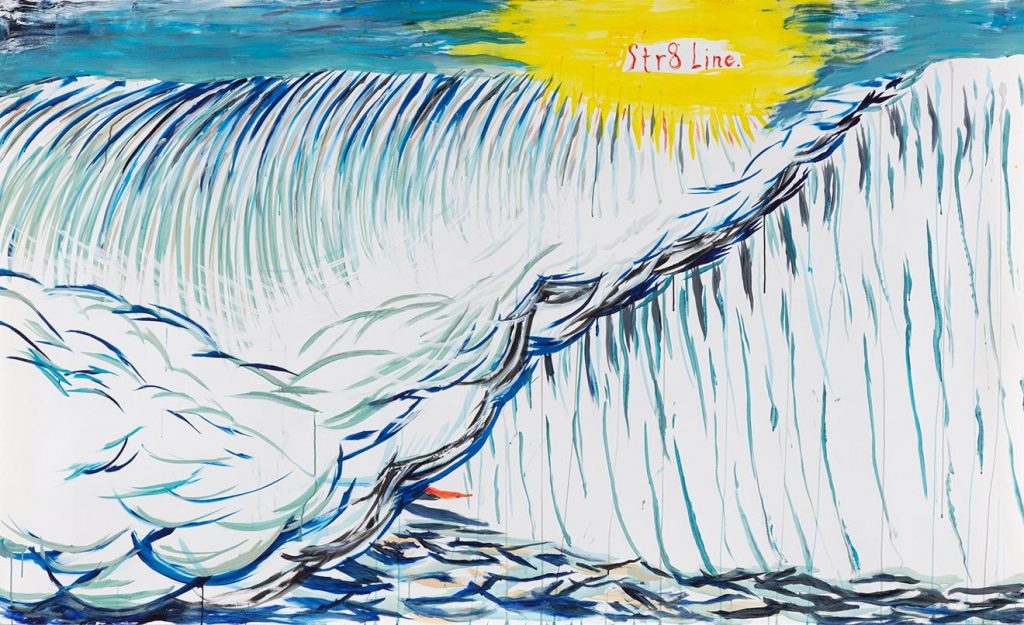

Raymond Pettibon has been returning to the themes of big waves, baseball, Gumby, religion and art since the 1980s, always working in a seemingly casual style of pen and ink, acrylic and charcoal, on paper, and occasionally, collage. Usually, they are tacked to the wall, unframed. His method for accessing endlessly new meaning in his themes is not by looking for the new, nor bowing to external pressure to scale up, use other media, or tap into the latest trend. He only bows to his own internal pressure and that is considerable. The show at Regen Projects is nominally dedicated to Pacific Ocean Pop with unusually large renderings of crashing surf but his familiar subjects act like launching pads for volleys of arcane, funny, poetic and racy texts.

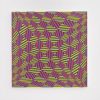

No Title (Str8 Line.)

2020

The works in this show are arranged in thematic clusters, as they were in his 1999 retrospective at Moca. I interviewed Pettibon back then at his family home in Redondo Beach. (He now lives in New York.)

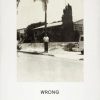

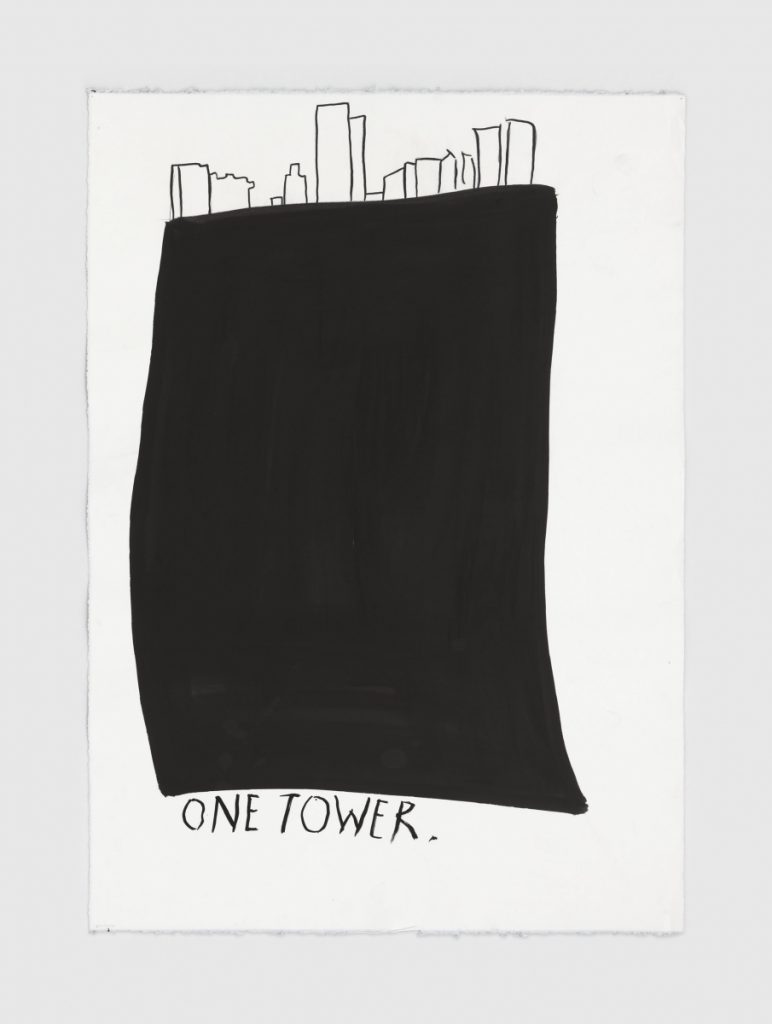

No Title (One tower.)

2020

A lot of his thoughts from 21 years ago still seem pertinent to this show. It was originally published as “A Creative Churning,” in the L.A. Times. All images here are from the past year and on view at Regen Projects through Oct. 31.

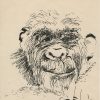

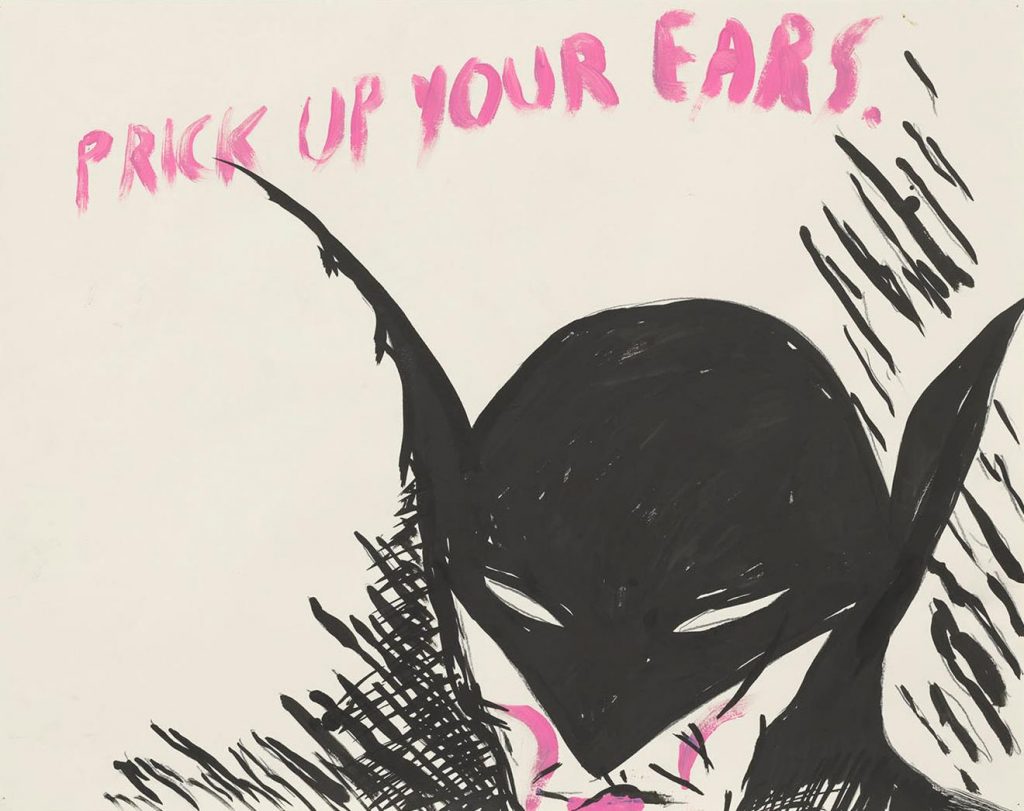

No Title (Prick up your)

2020

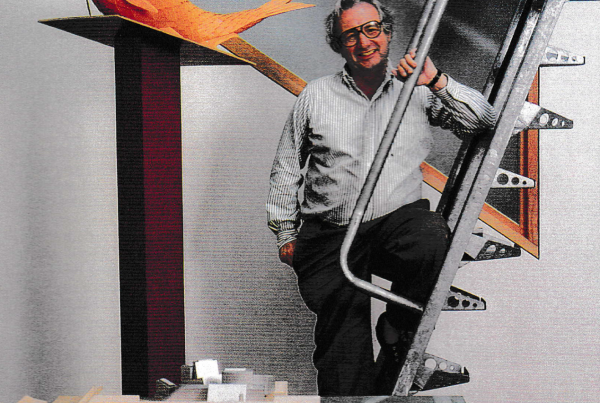

Two blocks from the coast in Redondo Beach, in a neighborhood largely landscaped with surf shops and strip malls, Raymond Pettibon quietly churns out stacks of ink drawings that garner praise from the most discerning international art critics and collectors.

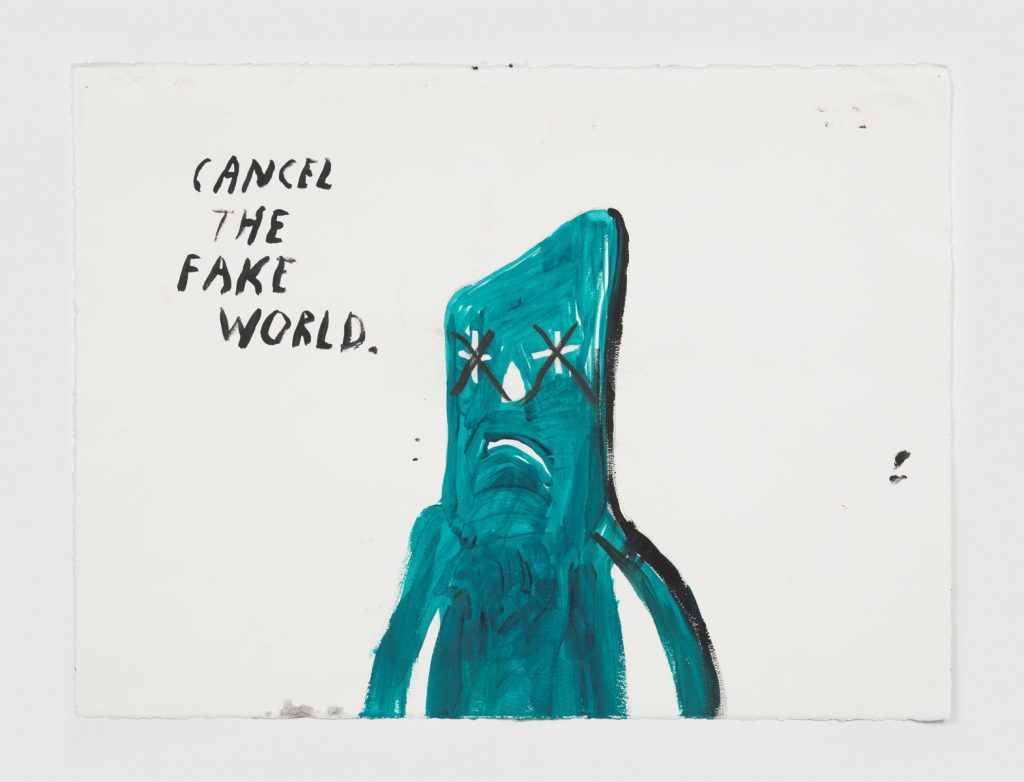

No Title (Cancel the fake)

2019

Certain subjects have caught his fancy over the years, including railroad trains, towering waves, loose women, hardened men, Jesus Christ, Charles Manson, Babe Ruth and Gumby. They are rendered in graphic styles that range from academic realism to comic-book. He captions these renderings with oblique and speculative observations written in differing voices, such as the formal syntax of the 19th century or the staccato parlance of the detective story. In the process, Pettibon borrows in style and substance from authors and artists as diverse as Mickey Spillane and John Ruskin.

A genuine eccentric, he has been compared to assemblage artist Joseph Cornell and 19th century symbolist Albert Pinkham Ryder. Pettibon melds his affection for the refinements of the past with the concerns of the present. He admits using pictures and language from the past as a distancing device, saying, “History didn’t begin for me with the abstract art of the 1950s.”

A genuine eccentric, he has been compared to assemblage artist Joseph Cornell and 19th century symbolist Albert Pinkham Ryder. Pettibon melds his affection for the refinements of the past with the concerns of the present. He admits using pictures and language from the past as a distancing device, saying, “History didn’t begin for me with the abstract art of the 1950s.”

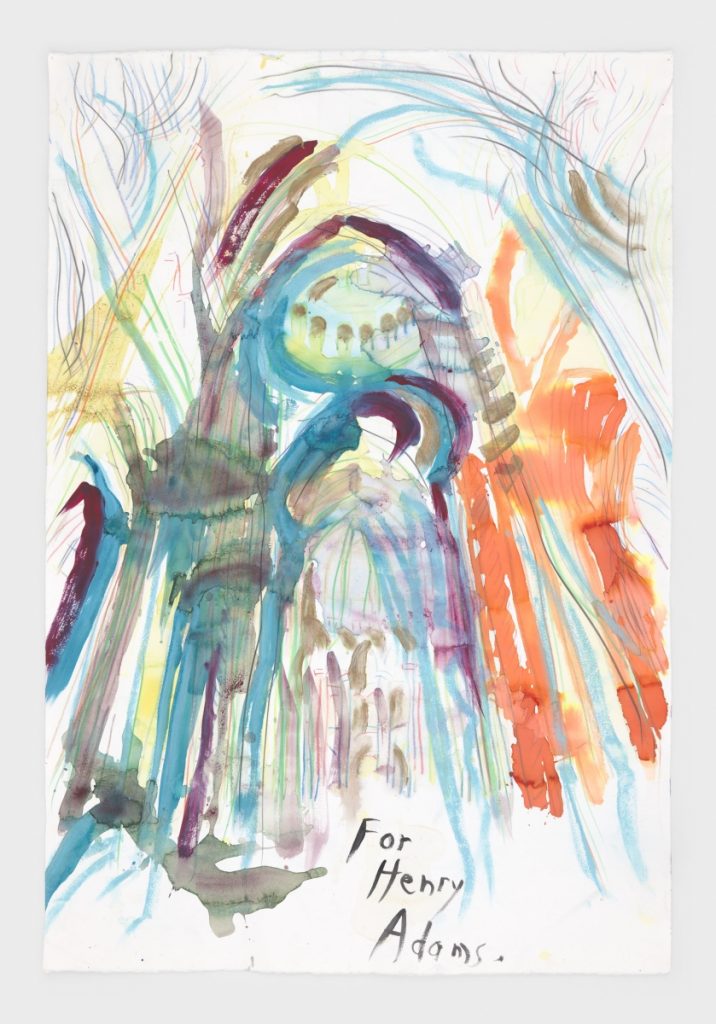

No Title (For Henry Adams.)

2020

A survey of Pettibon’s drawings and watercolors, along with the books and pamphlets he produces, opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art today. Organized by Ann Temkin, a curator of 20th century art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Suzanne Ghez, director of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, the exhibition includes some 500 of the 7,000 works Pettibon has made over the past two decades.

After reviewing some 3,000 drawings for the show, Temkin came to understand something of Pettibon’s prolific nature: “It’s not about the art industry. It’s about someone working in a way that is central to their whole existence.” At the Philadelphia Museum, Temkin installed Pettibon’s works according to their present ownership, with each grouping under the name of the collector–L.A.’s Barry Sloan and Gilbert B. Friesen and New York art dealer Barbara Gladstone, among them.

Of this unconventional approach, Temkin said, “It struck us forcefully how these collectors had tapped into different veins of Raymond’s work. They almost became collaborators in the manner they put together whatever they chose.”

MOCA’s chief curator Paul Schimmel is hanging the show in the same way here, though adding some 30 pictures owned by Southern California collector Arnold Ford. Schimmel further customized the presentation by asking Pettibon to complete a half-dozen wall paintings as part of the installation in the museum’s Grand Avenue building.

Schimmel, who included Pettibon’s work in “Helter Skelter,” his 1992 survey of the darker side of L.A. art, waxes enthusiastic about the artist. “It’s important to remember that he is a draftsman in the clear sense of drawing directly from his imagination onto a piece of paper. He has no equal in that respect. He is admired by the other artists of his generation, like Mike Kelley or Jim Shaw, because he is an absolute natural. The work literally pours out of him.”

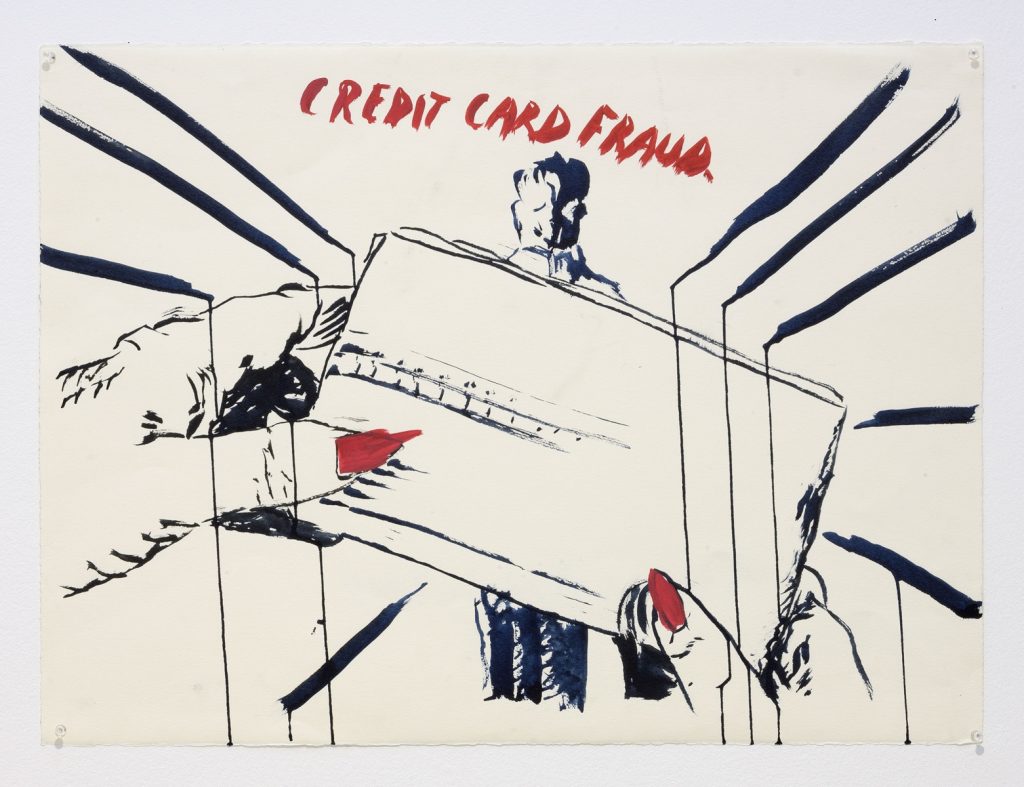

No Title (Credit card fraud.)

2019

Outfitted in surfer shorts and T-shirt, the 42-year-old artist has curling black hair, graying at the temples. He flops into a rattan chair in his living room and stares out the window as he talks about his work. Sentences start, then trail off. Despite the curators’ faith in his drawing abilities, Pettibon says that writing comes more naturally to him. “The drawing is more of a chore, though when I am actually doing it, it can be a pleasure. But what I like best is definitely the writing.

“Sometimes I have this fantasy that in the long run, it can work as a diary that will sum up my life and thoughts,” he explains. “Yet, that would take longer than I have on Earth. There would always be something more to be said. It could never be summed up, there would always be some qualification. It’s like mathematics. There is always some number like pi; it’s never finalized.”

No Title (So full o’)

2020

Pettibon’s analogy is not coincidental. He graduated from UCLA at age 19 with a degree in economics. He approaches literature, philosophy, theology and aesthetics as a theoretician might systematically try to solve a problem. Instead of a linear progression, the artist lets his diverse readings suggest what he needs to write or quote and then adds it to a previously completed drawing, though his process is never exact. “When I see a train, I want to take it in my arms” captions his drawing of an old-fashioned locomotive. A graphic arrangement of five phalluses silhouetted against a white background bears the dry observation, “We share a wide community of belief.”

His unstructured process lends a poetic openness and unpredictability to completed works on paper. “Sometimes it can be kind of infuriating, the way that there is always some kind of qualification to any problem,” he says.

No Title

2020

Indeed, Pettibon began his career as an artist by drawing political cartoons in UCLA’s newspaper, the Daily Bruin. When his older brother, Greg Ginn, founded the punk band Black Flag in the late ‘70s, Pettibon contributed drawings for their posters and album covers. His lurid illustrations initially attracted the attention of artist Mike Kelley, who became a friend and supporter. These days, Pettibon distances his work from the punk music movement, and his interests and techniques have grown more refined.

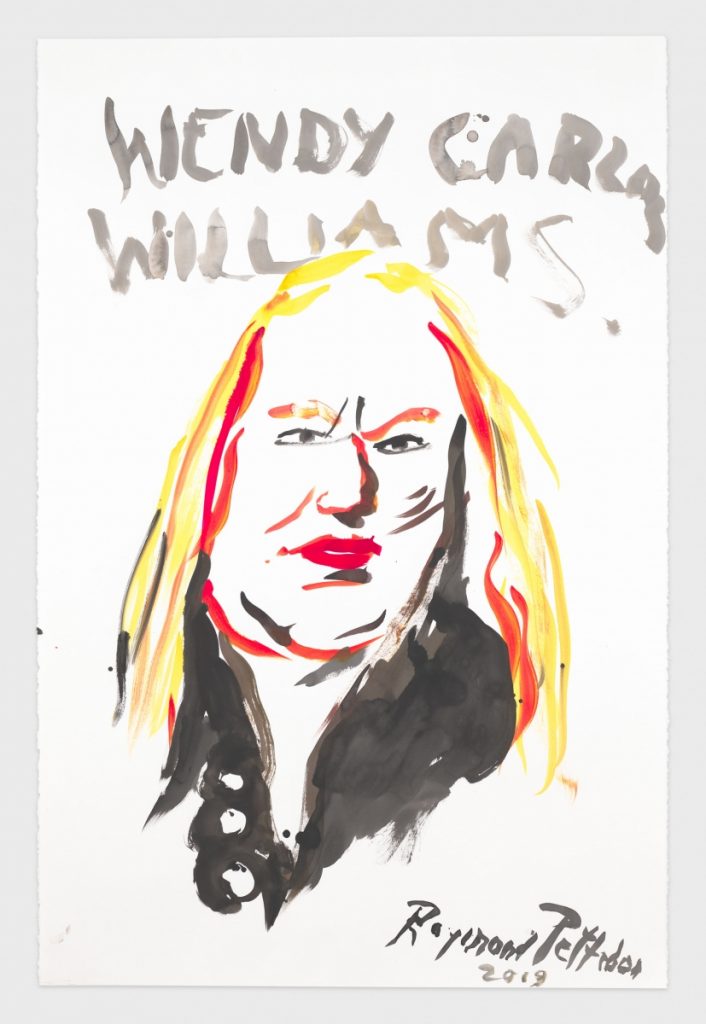

No Title (Wendy Carlos Williams.)

2019

Instead of a conventional museum catalog, the show is accompanied by a “reader” of selected writings enjoyed by the artist. The fascinating compilation of excerpts from larger works includes lists of names by Henry James, an essay on the brush stroke by Robert Henri, “The Library of Babel” by Jorge Luis Borges, and Ring Lardner on baseball.

Picking up the “reader” and flipping the pages back and forth, Pettibon says, “I don’t think since I’ve been a teenager have I read a book from beginning to end by getting caught up in the plot. I kind of wander away en route. The kinds of books I like to read seem to be obscure and boring works of philosophy and criticism. In my case, there is too much going on in the interim. Obviously, I borrow quite a bit from them in my own work, and it’s not just a matter of editing. It becomes my context.”

No Title (The pages are)

2020

Despite recurring themes, Pettibon doesn’t plan for any particular drawing to be part of a series. “My first drawing of a train was not done with the foresight that there were going to be more. When that happens, it takes on a life of its own, it strikes a nerve and I turn out to have more to say on a subject than one drawing can contain.”

*

The artist grew up in the Redondo Beach area and now lives in a beige stucco house with his mother and father, Oie and Regis Ginn. The living and dining room that serve as Pettibon’s studio are cluttered with piles of drawings, magazines and, more than anything else, books. Stacked on the dining table, next to bottles of ink, pens and brushes, are Benvenuto Cellini’s biography, several volumes on baseball players, a recent horse racing sheet and a few comics. One shelf contains his expanding collection of old wooden tennis rackets, while a corner cabinet is filled with porcelain cups and plates that were delicately painted by his grandmother.

Three dogs scamper about. The elder cocker spaniel is besotted with Pettibon. The artist picks her up and obligingly scratches her behind the ears. “We got her from the pound and could see that she was a good dog but she had no papers. So we called her Vaguely Noble, after a famous racehorse,” Pettibon explains. This sort of wordplay was extended to the naming of the longhair dachshund, also rescued from the pound and named Barely Noble. The younger cocker is named for the word “untitled” in German, a moniker dreamed up by Pettibon’s art dealer Shaun Caley Regen of Regen Projects.

All of this attention to names is clearly part of the household ambience. Indeed, Pettibon’s own nom de plume was coined by his father, an English teacher and author, who referred to his young son in French as something small and good: “Petit Bon.” The artist remembers that his mother used to read to him when he was young, so that he appreciates the discrete rhyming sounds of language. Despite the prestige of having a large-scale survey of his art come to his local museum, Pettibon remains blase. “I have a deadpan, unexpressive face,” he says, with surprising frankness, “which is actually the way I feel on the inside. I don’t get excited. I’ve never gotten excited. It’s my nature.

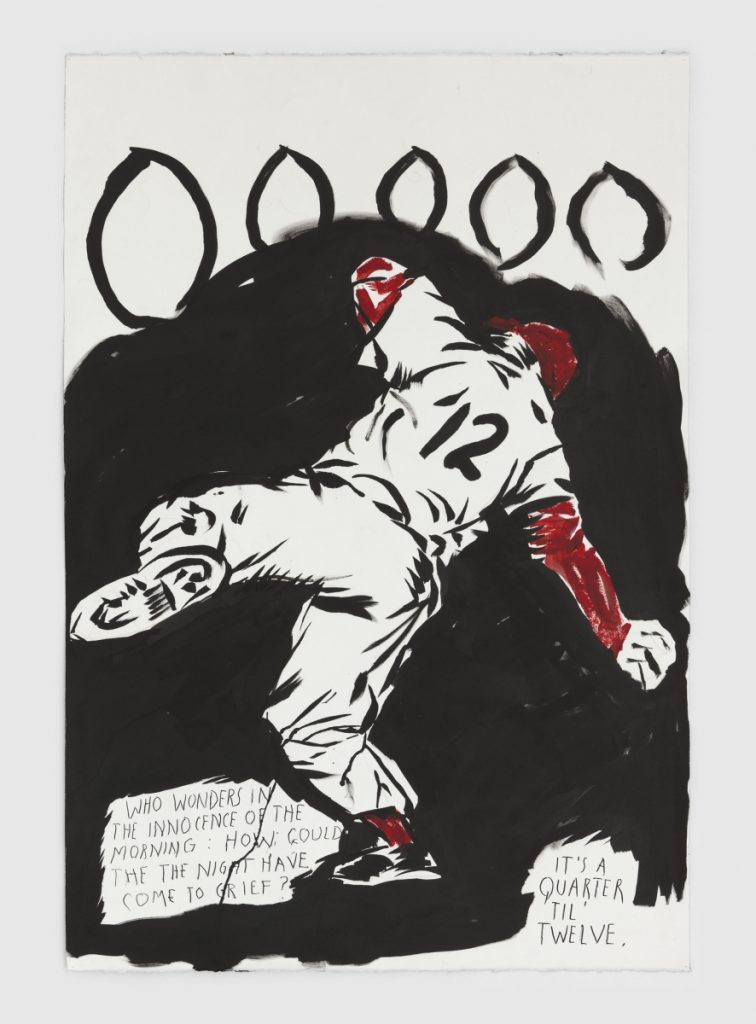

No Title (Who wonders in)

2020

“It’s like athletes these days. If they make a routine play, they jam their mitt up and make a big display. It used to be that if you hit a home run, you trotted around the bases with your head down, not showing up the other team. I thought it was more classy not to show up the other team. It’s not a conscious thing. That’s just my temperament.” *