It is worth recalling that L.A. did not have an independent art museum until 1965. Art exhibitions, some of great interest or value, took place in a wing of the 1913 Museum of Natural History, Science and Art in Exposition Park. The dramatic rise in post-war financial success led civic leaders to raise funds for the downtown Music Center and Hancock Park based LACMA, both built in the popular mid-‘60s style of a cultural shopping mall with open plazas and reflecting pools, pavilions for concerts and pavilions for art.

The very first director of LACMA, the highly respected Richard Brown, quickly found himself at odds with the board over his choice of architect for the new museum: Mies van der Rohe. He lost the battle and L.A.-based William Pereira was chosen instead.

Museum directors everywhere are confounded by the fact that they are both leaders and servants, caught between seemingly ungrateful constituencies: wealthy patrons and waspish artists, curators and critics.

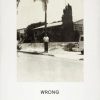

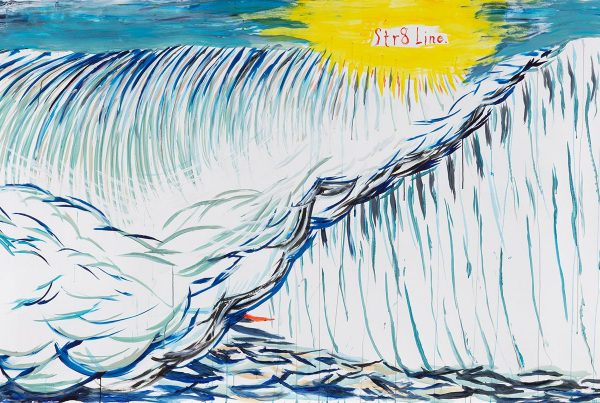

The battle continues as Govan faces baffling criticism for the demolition of the outmoded Pereira building, long disliked by artists, critics, curators and the general public. Exhibit A? Ed Ruscha’s painting of the building going up in flames, which he started in 1965, the year the museum opened.

Hence, I sensed it might be worth asking the man bearing the brunt of this weight to clarify a few questions.

Hence, I sensed it might be worth asking the man bearing the brunt of this weight to clarify a few questions.

Michael Govan met me in his office on the 14th floor of 5900 Wilshire Boulevard. The offices of LACMA as well as the library are in the process of being moved to the high rise building across the street from the museum. Dressed in his customary dark suit and white shirt, Govan is at his desk at nine in the morning. After a friendly greeting, he glances out his office window to the morning sky and asks, “Did you see the transit of mercury across the sun?”

Me? “Uh, no.”

Govan adds enthusiastically, “It’s a very rare occasion when you see Venus or Mercury go across the Sun. That’s how they figured out the distance from the Earth to the Sun in the 1600s.”

This is not an unusual sally from Govan, who flies his own plane and is a passionate supporter of technically and logistically complex land art such as James Turrell’s Roden Crater in Arizona and Michael Heizer’s City in the Nevada desert. He is a true believer in the expansive view of art’s possibilities and ways in which that can be made available to the public.

With a degree in art history from Williams College, where he helped establish MassMoca, in 1988 Govan became deputy director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York at age 25 and working with Frank Gehry on building the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain. In 1994, he became director of Dia art foundation in New York where he led the transformation of a Nabisco box factory plant in the Hudson Valley into Dia: Beacon. Since becoming CEO and Wallis Annenberg director of LACMA in 2006, he has seen through the completion of the Broad Museum of Contemporary Art and the Resnick Pavilion, both designed by Renzo Piano. The two buildings added 100,000 square feet of gallery space to LACMA.

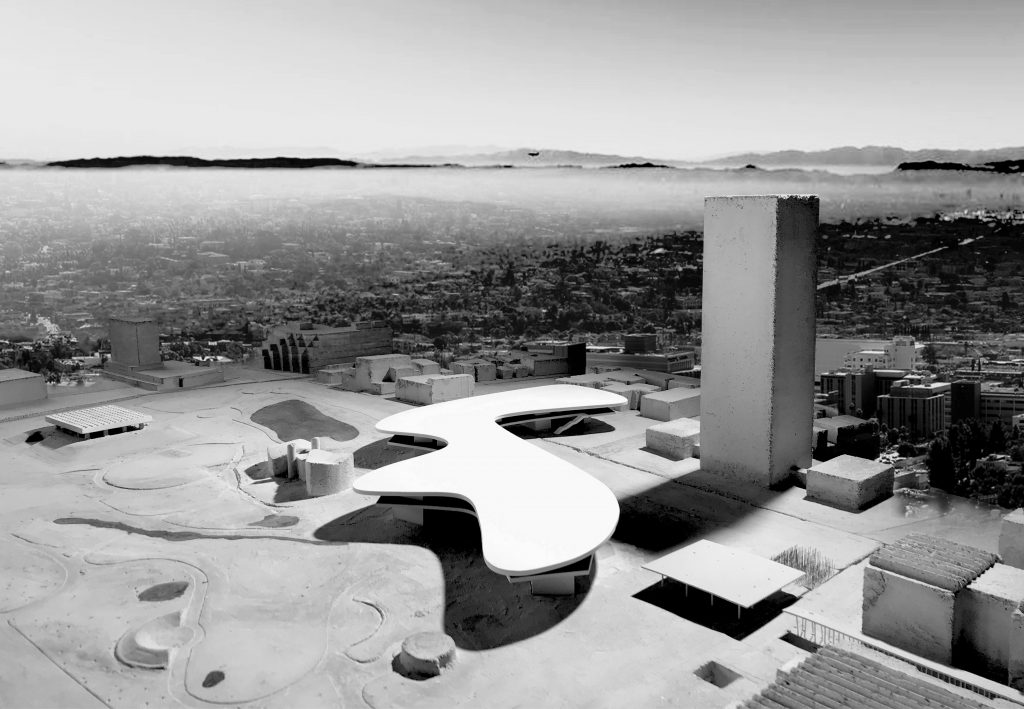

We are meeting to discuss the most challenging project of Govan’s career, the new structure designed by Peter Zumthor that will replace the original LACMA buildings erected by William Pereira in 1965 and the 1986 additions, including the brick and glass wall along the front of Wilshire Boulevard, by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer.

Until now, Govan has tried to focus on the Zumthor project and its challenges. As a result, assumptions and indignations have piled up in print, online and in general conversation. Informal conversations and social media searches show that artists, collectors, critics, architects, museum-goers and others seem equally divided against or in support of the curvilinear, single-story building mounted on thick legs above the park.

It will house LACMA’s varied yet uneven collections of European and American art, Asian art, pre-Columbian and post-Columbian art of Latin American, ancient art, art of the Middle East, decorative objects, furniture antique and recent, and, of course, modern and contemporary art.

Though considered an “encyclopedic museum,” LACMA is not the equivalent of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Not everything in LACMA’s collections is first rate or needs to be shown at all times.

In addition, the past decade has seen dramatically shifting priorities in the ways museums present their collections with a move way from the long galleries traditionally dedicated to national and chronological order. From the outset, Govan expected to incorporate such changes in LACMA’s new building as a 21st century museum.

In this slightly edited interview, Govan responds at length to many of the issues that have been broached by critics and concerned citizens. For example:

It is not the “incredibly shrinking museum,” as quipped on social media.

It is taking up less space, not more, in the La Brea Tar Pits Park to reduce impact on the ongoing work there.

Permanent collections will be on view but with greater integration and greater rotation to avoid the traditional long march of Western art history.

Collections donated as a group to the museum will continue to be shown together including the Carter Collection of 17th century Dutch landscapes as well as the Lazarof collection of modern art.

The museum is a single level structure to be both non-hierarchical and have less physical and visual impact on the park land.

Now for Govan’s own answers:

Now for Govan’s own answers:

HDP: Michael, we are meeting to get some perspective on what’s going on now at LACMA. I’d like to dive right in before turning to the history and the context. I would like to hear some of your feelings about the responses to this building project that you’ve been working on for eight years.

Govan: Over a decade if you include everything including the early discussions with the board.

HDP: It seems as though the most recent Peter Zumthor model was presented and immediately there was quite a lot of criticism about the square footage. That seems to be a recurring issue. Even on the LACMA website, it talks about how this building of 347,000 square feet is replacing 393,000 square feet. How did that decision come about?

Govan: Well, the goal was to reduce the square footage of the whole facility.

HDP: And why was that?

Govan: To lighten the load on the La Brea Tar Pits and create a better visitor experience for the park and the museum. Very few museums now incorporate a lot of storage inside their main facilities, especially when you have Hancock Park, which is built on their three faults, where there is methane. Digging underground is really not recommended. So we kept the minimum underground. The tradition now is to have your own storage facilities outside. MoMA has a dozen. That was the first thing I did at the Guggenheim in the ‘80s, building our own storage facility. There’s no reason to store our works on site. It’s not even considered a good idea because you might as well have your art spread out. So the idea was to remove storage and remove offices because that’s not highest and best use in the park and also, it’s not cost effective, because if new museum construction with climate controlled buildings and a name architect and all that costs $1,400 a square foot, you just don’t want to build offices and storage in that framework when you can build them for a lot less.

So we decided that early on, which is very logical. It was decided to (concentrate on) the public facilities and the necessary additional auxiliary facilities: security, transit storage, catering kitchens for the three restaurants, you know, all the things you have to have on site, two loading docks, which we don’t have now, one for art and one for non-art. So we definitely made a lot of upgrades and increased facilities that were necessary to the site and then the logical thing is to move the offices off the site and move the storages off the site. So that was decided early on as a very good plan and it would also lighten the load of the building in the park.

In Los Angeles, we have very little green space and open space. A lot of things have changed in recent years including adding the whole city block of the May company building so now the park goes east and west and in a much larger direction, so we moved the weight around. The idea was to open it up because the park was just so tiny. It was just the Tar Pits.

Now we really have an urban park with the subway stop, the movie museum, 200,000 square feet of LACMA’s new facilities. The current facility blocks your way whereas you’d really like it much more integrated with the Tar Pits. I call it the ‘mammoths to movies’ park, right? So you could walk around in it. So that was the urban planning imperative of the early stages of the project. You wanted to open up Hancock Park, create this amazing space with all these cultural and natural history facilities and of course, you have the Peterson museum and everything else. It was a very specific goal and that was the point of the building. Maybe I should just address the square footage.

Now we really have an urban park with the subway stop, the movie museum, 200,000 square feet of LACMA’s new facilities. The current facility blocks your way whereas you’d really like it much more integrated with the Tar Pits. I call it the ‘mammoths to movies’ park, right? So you could walk around in it. So that was the urban planning imperative of the early stages of the project. You wanted to open up Hancock Park, create this amazing space with all these cultural and natural history facilities and of course, you have the Peterson museum and everything else. It was a very specific goal and that was the point of the building. Maybe I should just address the square footage.

HDP: Square footage, yes.

Govan: So your question was about the gallery square footage. So of course, I’m a builder. I like to build and build and build, I’ve always been building and I want more and more and more, that’s my whole life. But we had to replace the facilities and as it turned out, if we had made bigger public spaces, such as galleries, we would have been subject to more problems with the environmental impact review. If you have more square footage of galleries, the argument is that there would be many more people etc, etc.

HDP: Now, let me just take a few moments for the layperson here. The impact review?

Govan: Yeah, the environmental impact review. You know there was resistance to any building here, obviously. So, yes, I imagined it could even be bigger because we were taking away the offices and the storage and all that. It turned out the way it needed to be was the same size replacement, which was the goal, by the way, and the biggest thing about the size, I have to say it never even occurred to me that it would be an issue because we had a long-term plan, we built 100,000 square feet first and then we would be replacing the other facilities. So essentially over the 20 years of my tenure or whatever, the goal was to double the size of LACMA. So coming in 2006, that was the goal.

HDP: So what was the square footage in 2006?

Govan: 110,000 square feet and essentially, we’re going to have 220,000 square feet of galleries and galleries, is all anybody cares about. I mean, yes, we have much more square footage and restaurants and public space and plazas and all that, but let’s just stick to galleries, and so when we’re done, we’ll have 220,000 square feet.

HDP: Of just gallery space?

Govan: Yeah.

HDP: That includes the 100,000 square feet of the Broad, Resnick and Goff buildings?

Govan: (And adding) 110,000 square feet of exhibition space.

HDP: In the new Zumthor building?

Govan: So the goal was to double the size of LACMA. Now this is – it’s why it was sort of hard for me to understand the criticism because it was very specific when in 2001, LACMA decided to tear down the structure for the Rem Koolhaas building. One of the major reasons that it was stopped was that you were going to close LACMA for five years and people were up in arms. I remember talking to Eli Broad about it and that was one of the big things. You’re not going to close LACMA for five years. Knowing that when I came on board in 2006, I sort of surprised everyone by not focusing on the old buildings and instead building the Resnick Pavilion in addition to the plans for Broad Contemporary Art Museum. Why did I do that? Because then you really had doubled the size of the museum and you would never close because with the Broad and Resnick and public plazas, you’re still like the largest art museum in the western United States. You’re bigger than the Getty, you’re bigger than the San Francisco Museum in one site, you’re bigger than almost every place.

So the idea is we would never close. That would never be a criticism and it would give us – it would double the size. The other reason to double the building first was knowing that the other facilities we’re going to be literally on their last legs. So we could develop an operating budget. It’s like exercise. You develop the muscles to run a bigger museum and you also build the attendance in relevance in Los Angeles to create the positive energy for the kind of fundraising lift that we were about to engage, which wasn’t really never been done before in LA.

So the logic was, build the Resnick Pavilion in addition to BCAM, now you’re safe, you never close. You double the size of the museum, so the museum can learn to operate a bigger facility. So then you don’t have to worry about if you can operate that facility, you can operate a facility with a new building, which will actually be cheaper to operate because we won’t have as much deferred maintenance, the energy costs will be lower and so from an operating model, you really have learned to do it. That’s really important because a lot of times museums expand and then they falter because they don’t have the operating muscles. I mean, I know it’s money, but really it’s like it’s practice because it means your memberships and your development and your staff, all have to be practiced at that. So we did it in reverse, we doubled our size because we figured we could eke out some more years of the old buildings, barely, and now we know how to operate a museum at a $72 million annual budget.

So now when we replace it, you know, we run a new facility that doesn’t have the maintenance headaches that this facility does and it should be easier to operate LACMA than ever before because we’ve already trained to run this double-size museum. So it was all a very logical way to get to the end solution, which was how are you going to replace all LACMA’s facilities and think about it. It’s a daunting task. Back in 2001, the facilities were cooked. They did the complete analysis to show everybody that the buildings were past their prime, they were dangerous.

So it was already a lot to eke 19 more years out of them. But how are you going to do that? The Resnick Pavilion became the heart of the campus, the way to double the size, the way to grow LACMA and the end result is you have a balance and a more open park. So really, you’ve kind of made it all make sense. We liked the pavilions because we’re in Los Angeles and we love to be outside with gardens, but you can’t have 20 pavilions, right? It’s a nightmare.

It was the old Anderson, the Hammer, the Bing and the Japanese Pavilion, right. So now you have too many pavilions and it is very, very, very hard to operate this double size museum right now because you have so many pavilions, entrances, ups and downs. So then the logical thing is let’s consolidate the four into one. Now you have four pavilions, which is what we had originally, which is manageable.

HDP: That includes the new Zumthor building?

Govan: The end will result in four pavilions, BCAM, (the Broad), the Resnick, the Zumthor, which is the Geffen Galleries, and the Japanese Pavilion, the Goff building. Four pavilions makes sense. But the seven pavilions was a security nightmare. So it was all part of a very, very, very thought out plan to figure out how in the world you were going to get this done.

From the beginning, the board (thought) that we should do something unique for Los Angeles. With the Broad and Resnick, we had Renzo Piano’s architecture. We should do something more unique and so I threw in the Peter Zumthor option.

You couldn’t renovate the original buildings. Those buildings belong to the county. They’ve been under maintained by the county, there is much deferred maintenance and plus it doesn’t even matter because this is what I’ve learned in LA: the seismic retrofit is the cost of the building sometimes. This is one of the toughest places to build. You have three faults, methane level five and these buildings don’t have any methane barriers. The new buildings do of course and that’s why we’re retrofitting the Japanese Pavilion now with new methane alarms and all of that.

You couldn’t renovate the original buildings. Those buildings belong to the county. They’ve been under maintained by the county, there is much deferred maintenance and plus it doesn’t even matter because this is what I’ve learned in LA: the seismic retrofit is the cost of the building sometimes. This is one of the toughest places to build. You have three faults, methane level five and these buildings don’t have any methane barriers. The new buildings do of course and that’s why we’re retrofitting the Japanese Pavilion now with new methane alarms and all of that.

HDP: And just quickly what is a methane barrier?

Govan: It just means that the methane gases can’t get into the building and you have alarms and sensors everywhere. Obviously, methane is very flammable as well was toxic. So every new building that’s built today in this area has methane alarms, and has barriers. Also, we’re on a 12-foot water table. So you have to really – the water barriers have to be very strong in this area. So it’s not the best area to build in honestly, but the museum is already here. So what are we going to do?

HDP: How did you choose the architect? Clearly Zumthor is your first choice, but he’d never done anything this big or anything like this. Do you slightly regret having that kind of architect to take on this project?

Govan: No, I have no regrets. You know, it’s funny I’ve worked with so many architects. I mean, I had the great pleasure of working directly with Frank Gehry in a way twice because in the ‘80s, he worked on the MassMoca project with Robert Venturi and SOM (Skidmore Owens & Merrill), so that’s when I met him. And then I had the pleasure of working with him on the Bilbao project. That’s when I learned to love Los Angeles by spending time with him and his client Jay Chaitt, who I knew really well later. Obviously I had worked with a lot of architects. I mean, I can give you a long list, but from the Gwathmey-Siegel to Arata Isozaki to Zaha Hadid.

HDP: But why Zumthor? He’s only known for one pristine museum.

Govan: Two.

HDP: Two.

Govan: So, the way I connected with Peter Zumthor is very simple. We were thinking about building a very large pavilion at Dia: Beacon for Walter De Maria’s I Ching. It’s a huge sculpture, it required 260 feet by 260 feet clear.

HDP: I see, okay.

Govan: And it was through discussions with Walter De Maria that we looked at a list of architects and the true story is that (curator) Lynne Cooke had just come back from Kunsthaus Bregenz, (Austria) and she said you know (Zumthor has done) an extraordinary museum and you should put his name on the list. It turned out that the only architect Walter De Maria had kept a file on was Peter Zumthor. He’s the only one he cared about. We ended up visiting every single building he had made and learned a lot about his architecture. We learned that no two buildings were the same. Every building was a response to its site in a very direct way and it was right at that time that he was commissioned to build the museum in Cologne.

Both museums are sublime and when you talk to artists about them and a lot of curators, they’re just considered among the most beautiful museums on earth. The De Maria building never was made and everyone said, “Oh, he can’t build a big building. He makes chapels and little museums.” But nobody’s born to make big buildings. Frank (Gehry) started small. Norman Foster started small. They all started small. What happens with architects is that at some point, they get their breakthrough and they make something big, but we had a test case, which is the Walter De Maria building and I paired him with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill because he needed a New York architect. He did really well and he designed an American building. Large spans, big open space, engineered in collaboration with SOM and his own engineers. It was a really sublime and beautiful big space that you could say was really worthy of this American artist who was thinking big.

You want somebody for LA that would be again as unique as Disney Hall. You want somebody different and it seemed like Zumthor fit the bill. I didn’t know if he would pass the tests and get to the end, but he fit the bill as somebody who would be very unique and responsive to the complex site. He had two museums under his belt that were fairly large, one with contemporary art and then one with older objects.

In Cologne, (Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum, formerly the Diocesan Museum) they have some contemporary art, but they have mostly older art from the Diocesan collection, and built over ruins. So he knew ancient art, he knew modern art. He had built two beautiful buildings. He was at that perfect stage in life. He was 65. That’s like prime moment for architects and he was especially well loved in the art community. So he seemed the right mix for the complexities of the site in the Tar Pits. He was very sensitive to site, so that was key.

HDP: And the complexities?

HDP: And the complexities?

Govan: The thing that characterizes his buildings is a sort of gravitas created through light and shadow that seemed necessary to honor these objects that we have in Los Angeles. I mean, we have precious ancient beautiful things: Assyrian reliefs, European paintings and beautiful things. His building seemed to give a kind of gravitas to that and part of that is the use of real materials.

HDP: What do you mean by real materials?

Govan: When you travel the world, you see there’s this sense of how modern architects have used stones, steel, glass, actually to create something akin to ancientness or a frame that feels timeless, not built out of stone, but built out of concrete or travertine or whatever is that has that quality to it. The joke in the art world about Peter Zumthor is that he makes the fire extinguisher look like a sculpture because he’s so good at this and if you go to Cologne, you go to Bregenz, you see it. He had every single quality that we wanted for this project and the board really liked it. The big controversy in 2013 was the Tar Pits because they didn’t like the idea that the building used all the site and pushed into their space.

HDP: Right, which is understandable.

Govan: That was the controversy.

HDP: But you addressed that controversy by having him pull back.

Govan: They basically said we are not going to support you with this plan. They were very clear to us and then the County Board of Supervisors told us that there was enough space for both of us, we should work it out. So that’s when the old idea of crossing Wilshire Boulevard (emerged.) Actually, it is an idea that’s floated around for a long time. In fact, Frank Gehry was the first who proposed it in the ‘80s. So that idea came back and we thought, well, what if we crossed Wilshire Boulevard and used the space across the street?

HDP: So Zumthor pulled the design of the building back from the park to allow the Tar Pits to have more space. Is that what you’re saying?

Govan: Peter Zumthor had been familiar with working with very fragile sites and what he had done at first is sort of frame those sites and use architecture to highlight them. He was using a similar strategy, not touching them or not going around them, but kind of cantilevering toward them, giving you views of them. He described it as a love letter to the Tar Pits.

HDP: Okay, but the Tar Pits – but people didn’t love that.

Govan: They didn’t love him back. He said, ‘I wrote a love letter to the Tar Pits, they didn’t love me back.’ But then you have to get into the real hard science of it. They have mapped out what they call, I know this is so arcane, but it’s so important. It mapped out the hotspots, places where they thought they could find additional important things for science. They used to be digging for mammoths and sloths, sabertooth tigers, now they dig for micro organisms in climate change layers and understand how biology is changed by climate change because of the Ice Age. So they’re doing a lot of climate change research and they said, we want to dig more and not less. They wanted to move towards the museum. There was a lot of controversy when LACMA was first put here because the La Brea Tar Pits did not want LACMA here. The park was given for science and I guess Mr. Hancock’s arm was twisted to put the museum here.

HDP: Interesting.

Govan: There’s real science to it and the land is limited. That’s when Peter, we decided to look at going across the street. We presented it to them first.

HDP: To, who’s them?

Govan: The La Brea Tar Pits Natural History Museum. They were super excited. Not only did they love that we had listened and we were redesigning but that the way the building worked, it served as a sort of viewing platform for the whole park. They really liked the design. That’s how that design emerged and we went to the county and the city and people really liked it. They thought it would be a landmark and we knew that would be controversial.

What landmark hasn’t been controversial? But the whole point of it was to create more park space and to honor the boulevard and we looked at it carefully.

HDP: Now people are complaining that you no longer have the unbroken view on Wilshire Boulevard.

Govan: You never had one. You don’t have an unbroken view. We looked so carefully at this. If you’re down one mile on Wilshire Boulevard, you look at this corner because there’s a kink in the road and there’s a billboard over our parking lot. Because of the kink in the road, the view is stopped in both directions right here. So you’re not losing that view. It’s just not true.

HDP: So when people have concerns about the view and the bridge, you’re saying there was no straight through view.

Govan: No. There’s a kink in the boulevard. Now, instead of looking at a billboard or nothing, you’re looking at an art museum.

HDP: Now, when you talk about the bridge going over Wilshire, explain to me that design and what Zumthor did to make that design acceptable from your perspective?

Govan: The reason it works is that the museum in the first place, the main gallery space, was lifted up.

From 2013, before we went over Wilshire Boulevard. It has these strong pavilions and then it has the main gallery space above, right. So why did we do that? To create flow through the park because the La Brea Tar Pits was blocked.

HDP: And people will be able to walk under the building.

Govan: Exactly, really easily. You’re going to have it be so transparent. (You can see Chris Burden’s) Urban Light from the Natural History Museum. So you’re going to have all these fantastic views through the park. And when you’re on Wilshire, you’re not going to look at a brick wall, you’re going to look at the park. So this idea of opening the park to Wilshire was the strength of the design. So we really didn’t change the design. The design is still the same, which is a large gallery on these strong piers that have public services and amenities. It just goes over Wilshire. If you can walk under it, you can drive under it. Same thing, the building didn’t change.

HDP: But the building was swung to the south.

Govan: It didn’t change its concept. Of course, it changed its shape because instead of just hovering in the park, allowing views under it, now it hovers in the park over the boulevard with views through it into the park and down Wilshire.

HDP: And when the bridge comes over Wilshire, what’s the terminus on the south side of Wilshire?

Govan: So it’s not really a bridge in the sense that it’s just the museum. You know, it’s not like you enter a bridge. From the gallery perspective, you’ll be unaware of it unless you’re on the edges looking out of the window.

Govan: So it’s not really a bridge in the sense that it’s just the museum. You know, it’s not like you enter a bridge. From the gallery perspective, you’ll be unaware of it unless you’re on the edges looking out of the window.

HDP: When I look at the map that you have on your site, I see the bridge element going over Wilshire, the terminus ends in a theater.

Govan: Part of the reason to do the theater on this side is that it’s far away from the academy theaters. So it’s easier to run simultaneous events and not have them in conflict..

But to go back to the your first issue. We’re doubling the size of the museum and 220,000 square feet is a huge amount of space to pay to operate. And you really have to have much more attendance to justify more space.

HDP: At 220,000 square feet, what would be the operational budget?

Govan: I don’t know if I can break it down. I mean, this museum operates at about 70 to 75 million dollars a year.

HDP: Which is a lot of money.

Govan: It’s a lot of money on an operations basis. And right now, I cannot open my galleries into the evenings. They’re just not well enough attended. Part of that is the complicated structure of our galleries. Our belief is that the attendance will grow. And if I was going to do one more thing, I would expand hours, not square footage. A 220,000 square foot museum could be anywhere from a five to a ten hour experience, depending on how carefully you look at art. It’s huge. And I think the justification for a bigger museum here just doesn’t exist.

HDP: And about the operation’s budget. How much of that is subsidized by the county or the city?

Govan: The county’s about a twenty percent subsidy to all the money we spend here. All I want to say on the size issue, for people to say they want a bigger museum, I just don’t know where that comes from. I mean really, you mean the Metropolitan Museum, yes, but they have six million people coming.

HDP: Well, it comes from the people feeling like you’ve taken away 50,000 square foot of gallery space.

Govan: No, we haven’t taken it away. The truth is that we haven’t taken away anything.

HDP: So keeping clarifying.

Govan: You start in 2006 with 110,000 square feet, you end in 2024 with 220,000 square feet. What other math is there that’s relevant? The Environmental Impact Review is what caused the misunderstanding. It says we’re replacing 120,000 square feet of galleries with a 110,000 on that side of the campus.

HDP: Okay.

Govan: We have a total museum that is much bigger, but we did reduce the gallery space in the Zumthor. Now when it was challenged, which I was so shocked. It turned out we had cannibalized even more galleries than we thought for offices. I myself took away offices and opened up some more galleries. But it turned out we were running about 110,000 square feet in that side of the campus. But when we really looked at it, this is a replacement of space and the other two buildings, BCAM and Resnick, were an addition of space. So again, I don’t know what other math there is because when you’re looking at paying for the operating costs, doubling the size of the museum over 20 years, it’s a good goal. And of course, we’re going to have double the size with state of the art facilities. When we started, we had 110,000 square feet of galleries and terrible facilities and we added new facilities and now we’re replacing the terrible facilities with new facility. So over 20 years, you will have replaced and built and have 220,000 square feet of galleries that are state of the art. It seems like a great deal.

HDP: And also all the offices are now in long-term lease space at the 5900 building and that’s where they are going to stay.

Govan: If we want to build offices, we can. It just doesn’t make economic sense right now. We’ve doubled the size of the museum which is going to be a state of the art facility. With whole 20-year building project, the public will have paid for 15 percent of it.

It’s a huge win.

HDP: I think the size issue is clear but I also want talk about a few of the other issues that have come up. What about the use of concrete walls and potential installation challenges. I’d like you to explain to me why you don’t believe that?

Govan: I worked at the Guggenheim, New York, for six years. It’s all concrete. We put up shows every three months there. It’s never a big deal.

Govan: I worked at the Guggenheim, New York, for six years. It’s all concrete. We put up shows every three months there. It’s never a big deal.

They change them in Bregenz all the time and they haven’t had a problem. They’ve had eleven years, no issues.

HDP: Are the concrete walls in some way less supportable for heavy objects?

Govan: No. They’re more supportable, they’re stronger. The benefit of concrete walls is twofold. Most importantly, concrete walls create a sense of gravitas. So the art will feel really great and it will feel like there’s a sense of fixity in a beautiful way. They will look very, very different and that’s really important. Most of the art in our collections was made before sheetrock walls. They’re a new invention, they feel theatrical. The idea was to have part of the museum with concrete walls because it would create a deeper, more powerful, positive feeling for the artworks and that was a great thing.

Additionally, as codes have changed, moving walls, which we do all the time in these buildings, is very, very expensive. We’re in earthquake territory and there’s also a growing complaint in the museum field of the waste of building the equivalent of a house when you put up an exhibition and tear one down. Now, we will still do that just like they do in theater. There are places to keep building and rebuilding. But the idea that half the museum would be fixed walls and half the museum would be flexible walls is a really nice mix.

I think the best museums are ones that have a variety of spaces to do different kinds of things. So it really made sense to me, the Goff pavilion, the Zumthor and the Renzo Piano buildings. You had a little of everything: a super eccentric space, the gravitas of the concrete with the Zumthor-Louis Kahn style, and then you have the Renzo Piano rational grid of sheetrock that you can tear apart and rebuild theatrically. It seems like a nice mix.

HDP: What about the curving shape of the Zumthor building?

Govan: The two main pieces of the site are the Tar Pits and the Goff building, right? They’re the strongest elements and they are organic in shape. So the idea of an organically shaped building is fully within the range of our history of architecture, organic architecture. There’s nothing weird about that.

HDP: I wanted to move on to the other concern that’s been expressed about how the Carter collection of Dutch art will be shown.

Govan: The Carter collection has to be shown together.

We live by the terms of the agreement. We’re just going to do it. I mean, the gift is that at LACMA wherever it’s shown, it has to be shown together.

Now, whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, I will let you decide because, you know, there are ways the Carter collection could be relevant in different ways by being juxtaposed with other objects. I think that we have changed the way we show art a lot and the way curators think about art.

HDP: Yes, is there any other part of the permanent collection that has that restriction?

HDP: Yes, is there any other part of the permanent collection that has that restriction?

Govan: The Lazarof collection. It has some restrictions on it too.

HDP: And it will continue to be shown together?

Govan: Yes.

HDP: Okay. Let’s talk about the Perenchio collection.

What will be happening with regard to that?

Govan: So Jerry (Perenchio) died before he got to see everything resolved. It’s in the hands of the estate and generally the message is the same. If you build the building, the collection will come. So that is still the operating assumption. And John Perenchio, his son and the foundation has been very encouraging and very generous. They made a $25 million gift toward the building becoming a reality. So it wasn’t just like you have to build the building and you’’ll get the collection. They are helping to build the building.

HDP: And when the Perenchio collection comes, will it have to stay intact or will there be restrictions?

Govan: We’re going to work with the foundation to talk about how it gets exhibited. You know, when Jerry died, it was a very personal back and forth with Jerry and then he passed before he got a chance to resolve it all. So it is unresolved in a sense.

HDP: What about the issue of changing the hanging of your collections?

Govan: This has been a big conversation. This is the way the museum field is going. There’s a need to rethink art history across time and place looking at Latin America in relation to Asia, looking at the Americas in relation to Europe. It doesn’t make sense to have an absolute geographic or temporal layout of a collection in a permanent way, especially when your collections aren’t totally encyclopedic. They’re encyclopedic in the sense that we have works from many times in many places but we don’t have the sort of collection that has to do that.

One of the things I think people don’t understand about LACMA is that we’ve always changed our collections from day one because of what we started with and then we kept growing and collections kept getting added. You’ve been through 30 collection changes of where the European collections went in the time you’ve been in LA. There was a question asked about the Georges de La Tour and I said, ‘Well, it’s moved 11 times in 14 years as it is.’ So LACMA has always changed. The change in collections is really just a fact of a modern scholarship and curatorial practice and because our collections are still growing and changing. So it’s not controversial from the perspective of curators or from LACMA’s history.

HDP: Well, I think people seem to be concerned about losing the long, chronological display. When you think about your curators, have you come to terms with how you’re going to be reinstalling these collections?

Govan: That’s what we’re starting to do now. Curatorial scholarship has changed so much in the last decades. I mean that’s the exciting thing. The curators are already thinking this way. Things have to be juxtaposed and rethought in different ways over time. None of these things are new and they’re coming out of scholarship in curatorial practice.

HDP: But I think people are wondering how logistically you’re going to do this in these new galleries that you’re creating. Logistically, is it going to be a box with a Casta painting here and Rivera painting there or is it going to be a system where viewers will be encouraged to wander around to find those things?

Govan: Coherently.

HDP: Coherently, yes, but will there be a box or won’t there be a box? A rectilinear gallery showing a group of paintings or sculptures?

Govan: The museum is designed with 20 rooms that have no natural light at all, half the museum, so they can show works on paper and I think you’re going to see that more things get out of storage, get into the galleries. Obviously, that’s a big discussion. MoMA has also committed to that recently. It’s just the nature of where museums are going.

HDP: Do you feel like you’ve answered the questions I’ve asked you?

Govan: Again, we’re going to have a huge museum, as big as anybody here is willing to run. 220,000 square feet is a huge amount of space. It’s cost, between the two phases, is hundreds of millions of dollars, right? It seems exciting. If I were to dream of more, it would be for more accessibility. I would love to see the museum open later. But the bigger the museum, the less hours you can run because it’s the same money.

So all I’m saying is that even LACMA doesn’t want a bigger museum. We can’t manage it. It’s about the quality of experience, not about the size of experience and some museums have gotten too big to run. It’s caused real problems because you’re spending a lot of money on heat, light, power, maintenance and security instead of putting it into art. So we think it’s the right size.

All of this is considered a positive realization of a vision for LACMA that’s not monolithic because you have the diversity of spaces, the Goff Pavilion, the Zumthor Building, the Renzo Piano buildings, you have these multiple paradigms. It gives curators a lot to work with and it’s going to be huge, with indoor and outdoor spaces, gardens, public sculpture. I mean, we’ve worked really hard to create something magnificent for Los Angeles. I think people will be happy with it.

HDP: Do you have anything to say about the challenging aspect of museums in the Los Angeles in the contxt of its own history?

Govan: I don’t know. The outside perspective on Los Angeles is that it is adventuresome and it really loves new ideas. But as you can see, even on this project people sort of want to pull back to, you know, a standard box, something they’ve seen before. So the adventuresome, there’s pushback on that a little bit. Disney Hall was not embraced until later. So maybe it’s that the environment is like every other environment, but there are people here like Frank Gehry, and others, who push harder. These are the rebels you often speak about.